By Allison Joy

IRON RIVER — The cabin at the lake was never really my grandfather’s spot. I think he liked it enough, but Joe Bloom had a bum leg due to an old war injury. It made it difficult, and eventually impossible, for him to live an active lifestyle. He got around well, but not without a degree of perseverance. Though his grandchildren remember keenly the speed with which he could ascend the steps when things got rowdy upstairs.

Grandpa was more comfortable front row of the basketball court, standing before a classroom of English students at Rhinelander High School, or presiding over city council during his 12 years as mayor of Rhinelander, Wisconsin.

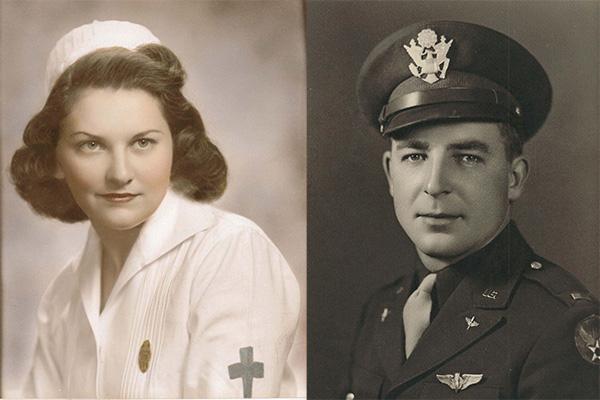

No, the cabin was Connie’s. My grandmother was a young army nurse cadet originally from Iron River and the cabin was located next door to the Rawnick family cabin built by my great-grandfather, Frank Rawnick, the former maintenance manager for the Hanna Mine Co. Joe and Connie met while Connie was in her nurse’s training at the army hospital in Galesburg, Ohio. There, she cared for Joe, a bombardier and returning from almost a year as a prisoner of war in Germany. The two would go on to marry in 1946 and raise three children in Rhinelander.

During the spring of 2020, I found myself holed up at the cabin much earlier in the season than I was accustomed to, due to the coronavirus pandemic. The ice was giving way and the loons had returned. They were at the start of a territory battle with a pair of swans for the island at the lake’s center. As expected, the loons prevailed.

I settled into Joe’s chair, a hard oak frame with heavy cushions, a long seat and accompanying ottoman that made it easier for him to get in and out of, while still retaining a classy finesse not found in an overstuffed recliner. Having just learned of a friend’s sudden passing, I sat feeling lost and disconnected.

Even though Joe had passed 21 years ago, a stack of his books remained beside his old chair. I picked one up called “Page One: Major Events 1920-1985 as Presented in The New York Times” and felt comforted. Journalism, and in particular local journalism, was a passion of mine. Reporting on Iron County has provided me a connection to my roots, and remembering my grandfather’s passion for news (he wrote a column called “Bloom’s Eye View” for Rhinelander's former Hodag Shopper) gave me a little boost of pride.

I opened the book and began to page through. A few sheets of yellowed paper slipped out, stapled together. “JOE BLOOM — P.O.W.” was typed at the top of the first page. I began to read the words my grandfather typed out five years before his passing, detailing war experiences I previously knew so little about.

“It started on December 7, 1941,” my grandfather wrote. “The war that we anticipated, but hoped would not come, had come. My involvement began in January of 1942 at lasted for 56 months. I enlisted in the Army Air Corps…”

Reading the words, I could hear his voice and even sense the cadence he employed when gearing up for some narrative oration.

Grandpa was trained as a bombardier in Roswell, New Mexico, starting out on the B-24 before serving as bombardier on the 10-person crew manning a B-17, one of 36 constituting the 390th Bomb Group.

“We were assigned to the European Theatre. On being based in Framingham, England, we began playing for keeps against Hitler’s boys … All in all, my crew and I had a total of 16 missions.”

On one of those missions, Grandpa and his men landed on the shores of Africa “with enough fuel left to stay in the air for eight more minutes. We had played it pretty close.”

His last mission targeted the heavily-defended sea port of Bremen, home to several large battle ships of the German Navy, including the Scharnhorst and the Tirpitsz.

“On the bomb run, our ship was hit and we were knocked out of formation. The anti-aircraft shell that hit us also got me in the left hip. Out of formation, we were attacked by several German fighter planes, and we were in a life-and-death struggle with them. I don’t know how many of them we got. I was reasonably sure I knocked down one.

“During the battle, our right wing gunner reported through the intercom that our right wing was on fire. While this was not confirmed, when someone says ‘fire’ the next command has to be ‘bail out’. I grabbed my parachute and headed for the escape hatch. I briefly checked the shroud tines on my chute. I also happen to glance at the altimeter and saw that we were just over 18,000 feet from the ground. Just as I left the ship, I counted to five and pulled my chute rip cord.”

Grandpa landed in a field outside of Bremen, along with the plane’s tail gunner who was uninjured. German civilians approached.

“I said to him, ‘Tony, for God’s sake, run.’ He said, ‘No, Lieutenant, I’ll stay with you.’

“Several of the civilians had guns, and things were touch and go for a minute. We knew that Germany respected the Geneva Accord, which protected P.O.W.s, but what these civilians would do, we were not sure.”

German soldiers appeared and scattered the civilian mob, and Grandpa and Tony were loaded into a truck that headed for a Bremen hospital.

“On the way, and just as we entered the city, we ran smack into a British night-bombing raid. We reached what we believed was a bomb shelter, but the guards got out and locked the doors of the truck. They left us there and for about the next hour, we could hear the bombs falling, and looking out, we could see the flares dropping.”

Eventually, the all-clear sounded. Joe survived the bombing and made it to the hospital in Bremen, where he stayed for 11 months and endured four failed attempts to remove the flak from his left hip, where the joint was badly smashed. In May of 1944, the German doctor informed my grandfather he was being commended for repatriation.

“That was the best news I had, when he came to my room to tell me that it was possible to send me back to America through the Red Cross. I can’t describe the feeling that gave me.”

He left the hospital in September of 1944, first for Nurenberg. A fellow traveler, Andy, “was one of the worst cases I have ever seen.”

Having bailed out of a B-24 as a top turret gunner, Andy’s chute failed to open until just 15 feet above the ground, breaking both legs and his back as well as his spine in two places and leaving him paralyzed from the waist down.

“I can remember the excruciating pain he was in when we were traveling from Bremen to Nurenberg … They had to move him several times, and I can remember his reaction to the pains he had when they moved him. Once, he said to me, ‘Joe, I don’t think I can stand being moved again.’ There wasn’t much I could say, but I knew that he had suffered terribly. I did say, ‘Andy, you’ve toughed it out this far. Hang on a little longer. Remember that going home covers a multitude of pain.’ He said he’d try. I believe he was one of the bravest boys I had ever known.”

Grandpa and a group of P.O.W.s were eventually exchanged for their German counterparts at the Island of Rugan. He boarded a Swedish liner, the Gripsholm, and after an initial stop in Liverpool it was another 17 days across the Atlantic to New York.

“The doctor came in to check us out,” Grandpa writes of the journey, “and he ordered immediate doses of medication, including the new miracle drug, penicillin. I began getting shots of that every three hours for seventeen days, and as a result, the infection I had began clearing up.”

Upon boarding the ship, Grandpa weighed a mere 117 pounds — compared to his normal weight of 170. But, due to the food aboard the ship, “which was really something,” he arrived in New York at 155 pounds.

He arrived on American soil via stretcher, where his mother was waiting for him. Eventually, he was transferred to the Mayo Army Hospital in Galesburg.

“At Mayo, I met several people, including the cadet nurses. One of them was Constance Rawnick from Iron River, Michigan. Later, after discharge, I married her. That was 50 years ago. We have three children — two boys, Jim and Tom, and a daughter, Rosemary. That number increased by nine, as each of them have three children. We returned to Rhinelander, where I have held a variety of jobs, including 12 years as mayor of this fair city.”

Connie ended her journey on this earth and returned to Joe on May 15 of this year. Their kindness, bravery and thirst for adventure live on in those they left behind.

Sitting in Grandpa Joe’s chair, reading those words he had written 25 years prior, was the closest I could come to speaking with him again, to have him regale me with a fresh riveting tale. Looking out across the lake, I felt him beside me. Looking ahead, I can only hope he and my grandmother find ways to visit me again.

It is from my grandfather I get my love of writing and from my grandmother, with whom I spent many summers, I get my reverence for the magic of this U.P. wilderness. She saw beauty in both the rare and the mundane. I will find her in the call of the loons, the smell of cedar burning in the fireplace, the sound of rain over the lake, and in the slivers of sunshine that cut through branches to light up a swampland. These woods are filled with her.